Dear Friends,

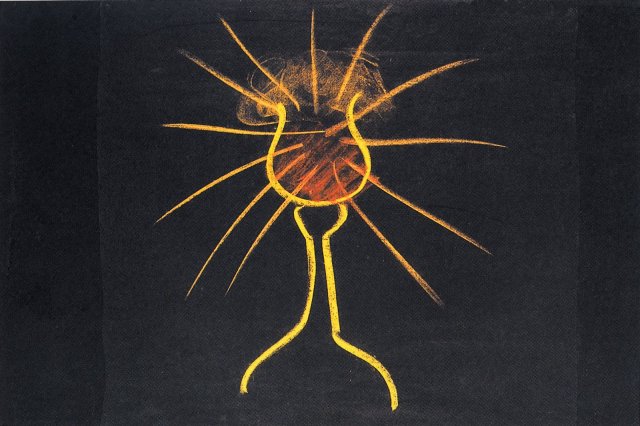

Teilhard de Chardin had a christic sense – an “extraordinary sense of the dynamic presence of Christ in the universe”. For him the Sacred Heart of Jesus was “the Heart of Christ at the heart of matter”. It was the “Golden Glow”. It was what he had earlier seen even as a child “gleaming at the heart of matter”.

Teilhard de Chardin had a christic sense – an “extraordinary sense of the dynamic presence of Christ in the universe”. For him the Sacred Heart of Jesus was “the Heart of Christ at the heart of matter”. It was the “Golden Glow”. It was what he had earlier seen even as a child “gleaming at the heart of matter”.

He had also a cosmic sense.

The whole of his life was very much, as he put it, a struggle that “was being produced at the innermost depths of my soul by the definitive coexistence and invincible reconciliation in my heart of the cosmic sense and the christic sense.”

It is important to understand that Teilhard does not see himself as the founder of a new philosophical or religious movement. For, as Robert Faricy writes: “The religious experience that lay at the base of the whole edifice of Teilhard’s thought was the devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus that he learned from his mother and, later, at school from his Jesuit teachers. Personal attachment to the Heart of Jesus is the seed of Teilhard’s Christology which, in turn, forms the most substantial part of his religious thought.”

It it also important to understand that, as Siôn Cowell writes in the article following, “he seeks … to proclaim the Christian message within the framework, not of a static, but of a dynamic universe–a universe, not in being, but in becoming.”

A dynamic universe becoming, we are moved to add, more and more the actual Body of God — and this by the power of the Sacred Heart — which is the power, in Teilhard’s terms, of the personalizing Personality.

Pax et bonum,

Randall Scott

The Cosmo Mystic

by Siôn Cowell

‘Christ must always be far greater than our greatest conception of the world’

‘The day will come when,

after harnessing space,

the winds,

the tides,

and gravitation,

we shall harness for God the energies of love.

And on that day,

for the second time in the history of the world,

we shall have discovered fire.’

Cosmo-mysticism

Teilhard speaks not only as a research scientist but also as a priest and poet who discerns with Meister Eckhart the ‘interdependency of all things.’ He shares with the medieval poet Dante the conviction that it is ‘love that moves the sun and the other stars.’

Claude Cuénot describes him as a ‘cosmo-mystic’ while Louis Barjon SJ speaks of him as ‘a mystic of the cosmos’ who rejoices in the wonder of an evolutionary creation that brings together love of God and love of the earth. He sees cosmic evolution telling us of the correlation between complexity and consciousness. ‘Consciousness,’ he says, ‘presents itself and requires to be treated, not as a particular and subsistent kind of entity, but as the “specific effect” of complexity.’

He combines scientific knowledge and mystical intuition to envision a universe in process towards its completion at a ‘centre of cosmic spiritualisation’ or ‘ultimate centre of personality and consciousness’ he calls Point Omega. And the Omega of Evolution, he believes, is none other than the Christ of Revelation: ‘The great cosmic attributes of Christ, those (particularly in St John and St Paul) which accord him a universal and final primacy over creation, these attributes only assume their full dimension in the setting of an evolution that is both spiritual and convergent.’

Evolutionary creation

Evolution, of course, is the key to Teilhard’s commitment as priest and scientist. He had been born at a time when evolution was far from being accepted by the Church. And, as we have seen already, it was the discovery of evolution that was to bring him up against the authorities in Rome. Everything that he had learned in science convinced him of the truth of evolution. If he was to write in support of evolution it was to make evolution credible to Christians. He saw evolution opening up a wholly new vision of the universe that was wholly compatible with catholic dogma.

‘Once upon a time everything seemed fixed and solid. Now, everything has begun to slide under our feet: mountains, continents, life and even matter itself … We no longer see the world revolving but a new world gradually changing colour, shape and even consciousness.’ ‘Within the space of two or three centuries … the universe no longer appears to us as an established harmony but has definitely taken on the appearance of a system in movement. No longer an order but a process. No longer cosmos but a cosmogenesis’

‘Evolution,’ Teilhard says in The Human Phenomenon, ‘is a light illuminating all facts, a curve that every line must follow.’ Evolution, he adds, is ‘no longer a hypothesis but a condition to which henceforth all hypotheses must conform.’ He always stresses the need for a clear distinction between the ‘two sources of knowledge: science and revelation. The mistake of theologians is to imagine that the two sources are independent … ‘ ‘Science,’ he adds, ‘will be progressively more impregnated by mysticism (in order, not to be directed, but to be animated by it).’

‘It is quite illusory for us to imagine,’ Teilhard argues, ‘that, having arrived at a better understanding of ourselves and the world, that we have no further need of religion … Numerous systems have been developed in which the existence of religion has been interpreted as a psychological phenomenon associated with the childhood of the human species. Religion can become an opium. It is too often understood as a simple antidote to our suffering. Its true purpose is to sustain and to spur on the progress of life … Religion represents the long unfolding, through the collective experience of humankind, of the existence of God.’

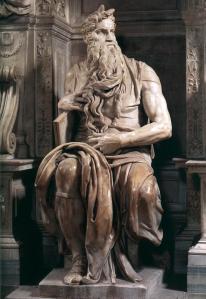

Humani generis

Teilhard may not have been mentioned by name in the encyclical Humani generis (1950) but passages on the instantaneous creation of the human soul and on original sin seem to have had Teilhard in mind. Teilhard responded with a short essay on the essential difference between monogenism (descent of humankind from a single couple) and monophyletism (descent of humankind from a single phylum): ‘In the encyclical Humani generis we hear discussed once again, with considerable passion … and confusion, the problem of the historical representation of human origins … ‘

‘The scientist cannot prove directly that the hypothesis of a single Adam should be rejected. But he can show indirectly that the hypothesis has been made scientifically untenable by everything we believe we presently know about the biological laws of “speciation” (or “genesis of species”) … This leaves us with two options. Either the essence of the scientific laws of speciation will change (which is hardly likely) or (which seems fully in accord with recent advances in exegesis) theologians will come to see one way or another that, in a universe as organically structured as ours where today we are in process of awakening a human solidarity far closer than the one they seek “in the bosom of Mother Eve,” is readily found in the extraordinary internal liaison of a world in a state of cosmo- and anthropogenesis around us.’

‘Christ,’ says Teilhard, ‘is the term of even the natural evolution of living beings; evolution is holy … ‘Evolution, by revealing a summit to the world, makes Christ possible – just as Christ, by giving sense (meaning and direction) to the world, makes evolution possible.’ Evolution helps us understand the cosmos and the Cosmic Christ of St John and St Paul and the Church Fathers without whom there would be no cosmos. ‘Evolution,’ suggests chaplain Charles Combaluzier, ‘has become the sole argument for the existence of God.’

Evolution and the Catholic Church

On 22 October 1996 John Paul II in an address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences confirmed what Pius XII had previously said in his encyclical Humani generis (1950) about the compatibility of evolution and catholic doctrine adding in words that echo those of Teilhard de Chardin that ‘new knowledge has led to the recognition of the theory of evolution as more than a hypothesis’. But, continued the Pope, ‘rather than the theory of evolution, we should speak of several theories of evolution.’ And here he warned against ‘materialist, reductionist and spiritualist interpretations’ that are clearly unacceptable to the Church. Teilhard would surely agree.

Wholism

By profession a palaeontologist, Teilhard stresses the fundamental unity of all things. He speaks to us today as a research scientist but his language is frequently poetic and his outlook wholistic. He raises the idea of wholism, first used expressis verbis by Jan Christiaan Smuts in 1926, to the level of an evolutionary doctrine of universal application to express the fundamental unity of all things.

He rejects the cartesian dualism between spirit and matter that has bedevilled human thinking since the Renaissance and Reformation: ‘There is neither spirit nor matter in the world … the “stuff of the universe” is spirit-matter. No other substance is capable of producing the human molecule.’

Coherence

Teilhard he was no modernist and he was certainly no concordist. What he seeks is coherence. ‘Avoid like the plague,’ he writes to Claude Cuénot, ‘any form of “concordism” that seeks to reconcile and justify what is possibly an ephemeral form of dogma and what is possibly also an ephemeral stage of the scientific view … On the other hand, try … to bring out and develop the basic coherence between what can already be regarded as the definitive axes of science and faith respectively.’

‘Religion and science,’ he adds elsewhere, ‘clearly represent, on the mental plane, two different meridians that it would be wrong not to separate (concordist mistake). But these meridians must necessarily meet at some pole of common vision (coherence): otherwise, everything in our field of thought and knowledge would collapse.’

Teilhard’s importance, however, lies not so much in his having attempted to reconcile the truths of modern science with the truths of Christian faith but, as Jesuit theologian Thomas King has rightly remarked, in his ‘exuberant claim that in the very act of scientifically achieving, he knew God.’ His mysticism is a mysticism of knowing.

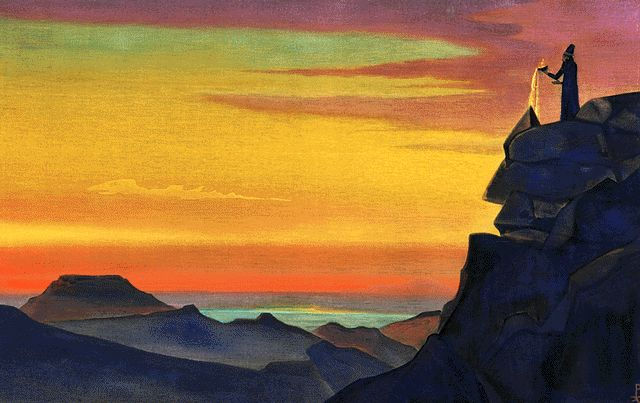

It is the fate of mystics to be much misunderstood and much maligned. They always have been. And no doubt they always will be. Teilhard is certainly no exception. Mystics often feel they have a problem putting into words what they see with what is often called the ‘inner eye.’ And yet they speak at great length about what they have seen. ‘It seems to me,’ Teilhard says, ‘a whole lifetime of effort would be nothing if only I could reveal for one instant what I see.’

He believes there is a fundamental distinction here between mystics and non-mystics, between ‘those who see, and those who do not.’ And yet there is always that nagging doubt, that element of uncertainty. ‘How is it,’ he asks in his final essay ‘The Christic’ (March 1955), ‘I find I am almost the only one of my type, the only one to have seen? And how is it, “when I come down from the mountain,” I find myself so little better, so little at peace, so incapable of expressing in my actions … that wonderful unity that encompasses me?’

Cosmic consciousness

Teilhard is one of that comparatively rare breed of men and women who have experienced what has been called ‘cosmic consciousness.’ Cosmic consciousness is a way of describing the mystical experience. It is characterised by a fundamental sense of oneness that seems common to most, if not all, mystical experiences – no matter how expressed. The medieval mystic St Mechthild of Magdeburg describes it well: ‘The day of my spiritual awakening was the day I saw – and knew I saw – all things in God and God in all things.’

Mystics often confess themselves bemused by the apparent inability of others to see what they can see so clearly. But – and this is important – true mystics never think themselves superior to others. They are humbled by their experience. And they come over as deep, creative thinkers ‘possessed with a desire to understand the universe.’ Teilhard de Chardin was undoubtedly one such thinker.

Cosmic sense

The cosmic sense – this extraordinary sense of oneness with the universe – was nurtured in his early years spent amidst the volcanic hills of his native Auvergne. It developed during his studies in England. And it blossomed in the trenches of the First World War to reach maturity in the long years of exile far from his native France.

Over the years he came to realise that, to ‘understand the world, knowledge is not enough, you must see it, touch it, live in its presence and drink the vital heat of existence in the very heart of reality.’ The mystic, says Thomas King, is ‘a reflection of the larger process going on in the universe; the mystic is a microcosm reflecting both the Many and the One found in the macrocosm.’

At the age of thirty, Teilhard tells us in his autobiography, ‘The Heart of Matter’ (1950), abandoning what he calls the old static dualism, he found himself emerging ‘into a universe in process, not only of evolution, but of directed evolution.’

It was, by any accounts, a dramatic change of perspective. His eyes were opened. He no longer saw a static but a dynamic universe. And he now began to see a way of resolving the latent conflict between the two senses – the cosmic and the christic – that had been simmering below the surface since his earliest childhood.

The cosmic sense he had grasped intuitively as a small boy. He was no more than six or seven years old, he tells us, when he began to feel himself drawn by matter or, more correctly, by something gleaming at the heart of matter. Once he came across a rusty old ploughpin. He was absolutely shocked to discover the fragility of matter.

Later on he came to see matter as ‘the matrix of spirit. Spirit is the higher state of matter … Matter is the matrix of consciousness and all around us consciousness, born of matter, is constantly advancing towards some ultra-human.’

Teilhard deals abundantly with the cosmic sense in his writings. He defines it as ‘the more or less confused affinity that binds us psychologically to the All which envelops us.’ He sees the cosmic sense lying ‘at the psychological root of all mysticism.’

‘The cosmic sense must have been born as soon as humanity found itself facing the forest, the sea and the stars. And since then we find evidence of it in all our experience of the great and the unbounded: in art, in poetry and in religion.’

Teilhard believes the more we try to comprehend the world along the lines of contemporary science, the more we find ourselves integrated within a network of cosmic inter-relationships. All things act on one another. Awareness of the essential unity of all things is integral to the act of knowing. ‘For everyone who thinks the universe forms a system endlessly linked in time and space.’

Christic sense

The christic sense – that equally extraordinary sense of the dynamic presence of Christ in the universe – he had learned as a child at his mother’s knee. He recalls, for example, his early attachment to the very catholic notion of the Sacred Heart of Jesus or, as he put it later, ‘the Heart of Christ at the heart of matter. The “Golden Glow”.’ This is what he had earlier seen ‘gleaming at the heart of matter.’

He tells us of the personal struggle that ‘was being produced at the innermost depths of my soul by the definitive coexistence and invincible reconciliation in my heart of the cosmic sense and the christic sense.’

The two senses – the cosmic and the christic – were to remain with him to his death sixty-five years later.

Complexity-consciousness

Teilhard sees all creation existing within a ‘divine milieu’ – a notion inspired by St Paul when he tells the Athenians: ‘In him we live and move and have our being’ (Acts 17.28). He uses the word ‘milieu’ in its French sense to express both centre and circle (or sphere). Hence the ‘divine milieu’ is both the divine centre and the divine circle, the divine heart and the divine sphere.

The creation story becomes the story of a universe that came into existence twelve to fifteen billion years ago and, as physicist Brian Swimme remarks, ‘has been complexifying ever since.’ Complexity or, more correctly, the correlation between complexity and consciousness is for Teilhard the key to the story of the universe.

‘Consciousness presents itself and requires to be treated … as the “specific effect” of complexity.’ Consciousness is truly a cosmic property. And the cosmic story is the story of a gradual but irreversible movement over billions of years towards ever-higher levels of what he calls ‘complexity-consciousness.’

‘Life is apparently nothing other than the privileged exaggeration of a fundamental cosmic drift … that we can call the “law of complexity-consciousness”.’ This is sometimes called ‘Teilhard’s Law…. The more complex a being, the more it is centred upon itself and, therefore, the more aware it becomes. In other words, the higher the degree of complexity in a living creature, the higher its consciousness, and vice versa.’

‘From the lowest to the highest level of the organic world,’ he continues, ‘there is a persistent and clearly defined thrust of animal forms towards species with more sensitive and more elaborate nervous systems.’ He develops his thinking on complexity-consciousness in essay after essay but especially in The Human Phenomenon – its correct English title – the book he wrote over two years between 1938 and 1940 but was unable to publish in his lifetime.

In his lifetime his superiors in the Society of Jesus simply could not accept its transdisciplinary approach despite every effort by Teilhard to overcome their objections. The Roman Curia tried but failed to prevent catholics reading it after he died. Within months of his death it had appeared on the bookshelves in France. It soon became an international bestseller.

Seeing

The Human Phenomenon should be read, Teilhard says, not as ‘a metaphysical work’ or as ‘some kind of theological essay, but solely and exclusively as a scientific study. The very choice of title,’ he continues, ‘makes this clear. It is a study of nothing but the phenomenon; but also, the whole of the phenomenon.’

Teilhard speaks as a scientist but we can see how ‘Teilhard the scientist’ easily becomes ‘Teilhard the mystic’ or even ‘Teilhard the Christian apologist.’ And many of those who are most critical of Teilhard are unhappy with the way he easily crosses the boundaries of science, philosophy and theology into the less well-defined fields of poetry and mysticism. But this is the virtue of Teilhard. And why he appeals to so many who are tired of the rigid lines of demarcation between academic disciplines.

He frequently puts what might be called today a ‘mystical spin’ on words like ‘knowing’ and ‘seeing’…. ‘Seeing,’ in fact, is a ‘keyword’ in Teilhard’s mystically-enriched vocabulary. ‘ … the whole of life,’ he says in the Prologue to The Human Phenomenon, ‘lies in seeing. To be more is to be more united. But unity grows only if it is supported by an increase of consciousness, of vision … True physics is that which will someday succeed in integrating the totality of the human being into a coherent representation of the world.’

He speaks of the system he develops in The Human Phenomenon as a ‘hyperphysics’ – an attempt at a correlation or correspondence between the views of science, philosophy and myth on origins and goals and the insights of theology on cosmic history.

He never saw The Human Phenomenon as an end in itself. ‘The Human Phenomenon,’ says Henri de Lubac, ‘was, in his mind, nothing more than a precursor to The Christian Phenomenon he never had the time to write.’

Enfolding and unfolding

Teilhard frequently uses the verb ‘englobe’ to express the idea of ‘enfolding’ within a globe, sphere or circle. This is something he shares in the context of a universe in evolution with the Rhineland cardinal and mystic Nicholas of Cusa who tells us, ‘the divine is the enfolding of the universe, and the universe is the unfolding of the divine.’

This is an image with which Teilhard would have felt perfectly at home. Indeed, it can be said that the words ‘enfolding’ and ‘unfolding’ are absolutely vital to understanding the thrust of his thinking. In his view ‘enfolding’ is even more fundamental to the evolutionary process than the traditional ‘unfolding’ of nineteenth-century thinkers. And he believes a physical (or material) ‘unfolding’ is quite meaningless unless it is accompanied by what he sees as a psychic (or spiritual) ‘enfolding.’ Nicholas of Cusa is, of course, but one of the great mystics who appear in Teilhard. He resonates with Meister Eckhart when he tells us: ‘God is a great underground river that no one can dam up and no one can stop.’

Teilhard shares with mystics down the ages a rejection of the idea that human beings alone are created in the image of God. The germ of consciousness is to be found in the most primitive of particles. It was present throughout the universe from the very beginning – something that gives new meaning to the cry of joy expressed by Blessed Angela di Foligno when she discovers ‘the whole universe is full of God.’

Groping

Teilhard frequently describes the evolutionary process as one of ‘groping’ – a progression by trial and error. ‘Groping is directed chance. It means pervading everything so as to try everything and trying everything so as to find everything.’

Among his many metaphors the idea or symbol of ‘groping’ is perhaps one of the most ingenious. It is pure Teilhard. It is dismissed by some and welcomed by others. Evolutionary geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky, for one, agrees it is more poetic than scientific yet, he says, ‘it is remarkably apposite.’ … ‘Without tentative gropings and without failures,’ Teilhard suggests, ‘without death, without planetary compression, as human beings, we would have remained stationary.’

But it is not evolution that is creative – and here Teilhard takes issue with one of his early mentors, Henri Bergson – but creation that is evolutive. He calls it ‘evolutionary creation.’ … ‘Evolution is not “creative” as science once believed but is the expression, in time and space, of our experience of creation.’

Noogenesis and noosphere

The cosmos or universe as we know it exists in duration in a state of genesis or generation. This is what he calls ‘cosmogenesis’ – the creative process that began twelve to fifteen thousand million years ago with the birth of the universe. All matter has what he calls an ‘inside’ or, more graphically, a ‘within’ – a rudimentary consciousness.

It is cosmogenesis which gives rise in time and space to the process he calls ‘noogenesis’ and to the sphere or layer he calls the ‘noosphere.’ He understands the ‘noosphere’ as the ‘sphere of spirit’ where ‘spirit’ is used in a particularly French sense to describe what we often call in English ‘mind and spirit.’

Teilhard’s cosmic sense convinced him noogenesis was a cosmic phenomenon. He had little doubt that what had been happening on Planet Earth over thousands of millions of years could equally well be happening elsewhere in the universe. In his day he could only speculate on the possible existence of what he calls other ‘noospheric systems.’ He thought their existence highly probable.

He believes noogenesis is, above all, a convergent process that is necessarily centred and cosmic in application. But – and this is important – a convergent process of psychic (or spiritual) ‘enfolding’ can only operate centre to centre in a process he calls ‘centrogenesis.’ ‘The principal of centrogenesis enables us to formulate, in its most intimate essence, the nature of cosmic evolution.’

Love

Teilhard sees love as the only known energy capable of uniting beings centre to centre. And he continues: ‘Not metaphorically, but in the truest sense of the term, the cosmic sense is – and can only be – love. In the cosmos it becomes possible, however unlikely the phrase may appear, to love the universe.’

He envisions love as ‘the most universal, the most formidable and the most mysterious of cosmic energies … the primitive and universal psychic energy … the very blood of spiritual evolution.’ … ‘Present (at least in rudimentary form) in all natural centres, living or pre-living, that make up the world, it also represents the deepest, the most direct, the most creative form of interaction that can be conceived between centres. In fact, it is the expression and the agent of universal synthesis.’

Omega and omegagenesis

Here we come up against what Teilhard sees as the psychological impossibility of a real love spreading itself directly from one human centre towards thousands of millions of other (faceless) centres across the globe. The only way, he thinks, we can hope to love so many centres on Planet Earth (and, potentially, elsewhere in the universe) is by loving one another in what he calls ‘a centre of centres’ – a centre to which he gives the name Omega – name consciously inspired by St John who speaks in Revelation of ‘the Alpha and the Omega … who is, who was, and who is to come’ (Rev 1.8 NJB). And this through the process he sometimes calls ‘omegagenesis.’ Omegagenesis, like noogenesis, may well be a cosmic process. But – and this is an important qualification – ‘there will only be one Omega.’

Omega he defines as ‘a centre different from all other centres which it “super-centres” by assimilating them; a person distinct from all other persons whom it fulfils by uniting them to itself. The world would not function if there were not somewhere ahead in time and space a “cosmic point omega” of total synthesis … Omega, he towards whom all things converge is reciprocally he from whom all things radiate.’ … ‘Omega itself,’ he says, ‘is discovered by us at the end of the process … of universal synthesis… ‘

‘With the discovery of Omega,’ he says in his autobiography, ‘was completed what I would call the natural branch of my inner trajectory in search of the ultimate consistency of the universe. Not only in the vague direction of “spirit,” but in the form of a well-defined supra-personal focus a heart of total matter was finally revealed to my experiential quest.’

Cosmic Christ

Teilhard the evolutionist now makes what we can only describe as a gigantic leap of faith by identifying the Omega of Evolution with the Christ of Revelation. And with this his cosmic sense becomes one with his christic sense. ‘Christic consciousness,’ he says, ‘keeps pace with and is required by the growing consciousness of humanity.’

Omega is identified with the Cosmic Christ who is the ‘Logos’ or ‘Word’ we find in the Prologue to the Gospel of St John (‘In the beginning … ‘) and St Paul’s Letter to the Colossians (‘All things have been created through him and for him … ‘).

The ‘Logos’ or ‘Creative Spirit’ – ‘the one who was, who is and who is to come’ – entered his creation by becoming part of the evolutionary process for which he himself is responsible. His purpose – to vivify or give life to his creation from ‘within’ and lead it towards its final completion and fulfilment.

This is the Parousia which Teilhard understands as the presence of the Cosmic Christ in glory at the end of time bringing together the ‘centre of centres,’ who is the term of the phenomenal universe, and ‘Christ-Omega,’ who consummates the totality of creation in the completion of his Mystical Body.

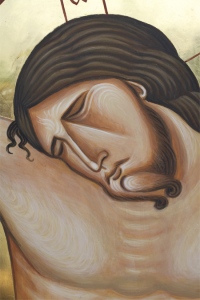

Christ is the focal point of Teilhard’s vision and the dynamic behind his search: ‘The mystical Christ, the Universal Christ of St Paul,’ Teilhard stresses, ‘has neither meaning nor value in our eyes except as an expression of the Christ who was born of Mary and who died on the Cross.’

Christogenesis and christosphere

Omegagenesis now appears more clearly as a ‘christogenesis’ and the ‘christosphere’ as the sphere of spheres – the sphere of the Cosmic Christ who embraces, penetrates and sustains the totality of the cosmos. As Jules Monchanin put it so well, ‘the christosphere is the goal of the noosphere.’

Teilhard shows an awareness of the teachings of the Greek Fathers that suggests an early introduction to the Cosmic Christ tradition that found expression in the Fathers like St Maximus the Confessor. Maximus placed it in the context of a static universe: Teilhard puts it in the context of an evolutionary universe: ‘Christ,’ he says, ‘has a cosmic body that extends throughout the universe.’

Teilhard’s Credo

Teilhard’s spirituality is, above all, a spirituality of engagement. It is based on his intimate conviction of God’s presence and, more immediately, Christ’s presence throughout the universe.

Teilhard’s spirituality is profoundly ignatian. Like every Jesuit he made The Spiritual Exercises every year. And like every Jesuit he would have recalled one of the best-known meditations: ‘What have I done for Christ? What am I doing for Christ? What should I be doing for Christ? I shall ponder on whatever comes to mind.’ Teilhard pondered long and hard. His concern as the years passed was to transpose the Exercises from the dimensions of cosmos to those of cosmogenesis – from those of a static universe to those of an evolutionary cosmos.

Robert Faricy puts it well: ‘The religious experience that lay at the base of the whole edifice of Teilhard’s thought was the devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus that he learned from his mother and, later, at school from his Jesuit teachers. Personal attachment to the Heart of Jesus is the seed of Teilhard’s Christology which, in turn, forms the most substantial part of his religious thought.’

Teilhard does not see himself as the founder of a new philosophical or religious movement. He seeks, rather, to proclaim the Christian message within the framework, not of a static, but of a dynamic universe – a universe, not in being, but in becoming.

He recognises the difficulty of encapsulating in a few words the breadth and depth of what he calls his ‘vision of cosmogenesis.’ … ‘My views hardly change,’ he says, ‘but have become simplified and intensely articulated in the interplay of what I call the two curves (or convergences) – the cosmic (natural) and the christic (supernatural).’

Teilhard attempted the impossible when he prefaced with a short statement of belief the 1934 essay he called most appropriately ‘How I Believe’:

‘I believe the universe is an evolution;

I believe evolution proceeds towards spirit;

I believe spirit, in human beings, completes itself in the personal;

I believe the supreme personal is the Universal Christ.’

Sin and evil

Teilhard is far from being the blind optimist some of his detractors would have us believe. He never denies the reality of sin or evil in the world. And wherever there is freedom, there will always be fault (‘culpa’). But he never forgets – as the biblical creation narratives remind us – that ‘original blessing’ came before ‘original sin.’ The story of the Fall – the story of the Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden – could thus be said to be the story, not only of hominisation, but also of human responsibility. Hence the corollary to complexity-consciousness is consciousness-responsibility.

This is not a facile faith in automatic progress but faith in a movement towards greater complexity-consciousness which involves both struggle and suffering, faith in progress which can only be achieved by responsible human effort and hence is fraught with human drama. A world in which there was no disorder would be a world which had already arrived at the term of its evolution (which, we must surely agree, is far from being the case).

The basis of Teilhard’s measured optimism is belief that being is better than non-being and awareness is better than non-awareness. Evolution is process; not necessarily progress: ‘evolution,’ as evolutionists themselves recognise, ‘can be retrogressive as well as progressive.’ For Teilhard, regression is the materialisation of spirit, progression the spiritualisation of matter.

Teilhard is far from accepting ‘a religion of progress’ or ‘a religion of evolutionary creation’ (Julian Huxley). And Jacques Maritain is quite wrong in suggesting Teilhard went in for a ‘cult of evolution, somewhat in the confused way of Julian Huxley’s evolutionism.’

Teilhard’s faith is nothing if not orthodox. Orthodoxy does not mean theological fixism. It does not mean sticking literally to formulations better suited to an earlier age – a point driven home by Pope John XXIII at the beginning of the Second Vatican Council. It means orthopraxis – pursuing the right course. ‘The essential quality of the orthodox evolution of dogma is to transform (objectively) divine reality without losing its quality of being objectively given.’

Concerned with both orthodoxy and fidelity to the Church, Teilhard seeks at all times to reconcile obedience with openness. He has no doubt about the importance of dogma. ‘One can only be a Christian by believing absolutely and definitively in all the dogmas.’ The least qualification or restriction and they would simply evaporate.

Christianity’s planetary and cosmic purpose

Teilhard reproached the theologians of his day for their failure to take account of the dimensions of a universe in process of evolution. He believed, above all, in the convergence of truth.

He has faith in an evolutionary creation because he has faith in the creator but also because his scientific research convinced him that evolution as such is meaningful and of absolute value. His faith is a faith enriched, not diminished, by his search for the unity of all knowledge, including scientific, philosophic and theological knowledge. ‘Science alone,’ he stresses, ‘cannot discover Christ. But Christ satisfies the yearnings that are born in our hearts in the school of science.’

‘As far as human origins are concerned, science certainly has a lot to discover and catholics a lot to think about. What we can foresee is that the Church will increasingly recognise the scientific validity of an evolutionary form of creation and science will make more room for the powers of spirit, liberty and, consequently, of “improbability” in the historical evolution of the world.’

Teilhard and the Church

In a letter to his friend Auguste Valensin SJ Teilhard writes: ‘I believe in the Church, mediatrix between God and the world.’ Faith in the Church is an extension of his faith in Christ. ‘We are fortunate,’ he tells Bruno de Solages in 1935, ‘to have the authority of the Church.’ And this from someone who, at first glance, might have felt unduly the weight of that authority!

Within the space-time continuum of human history he sees the Church as in organic continuity with its origins and as the centre from which the power of the Risen Christ reaches out to the whole of humankind. The Church is the Body of Christ. The Church is ‘the very axis on which the awaited movement of concentration and convergence can and must be effected.’

‘The Church, the reflectively christified portion of the world, the Church, the principal focus of interhuman affinities through super-charity, the Church, the central axis of universal convergence and the precise point of contact between the universe and Omega Point.’

The Church as the community of individuals incorporated in the Risen Body of Christ forms a ‘phylum’ (or ‘division’) within the human species. ‘The Church is phyletically essential to the completion of the human.’ He speaks of the Church as a ‘phylum of love’ to the extent that it has manifested in countless examples the possibility of a universal love.

It is impossible, he writes in his journal, ‘to have Christ without the Church … without the Church Christ either evaporates, crumbles or disappears … The dilemma remains: either catholicism or liberalism (that is, the negation of all certitude) … the liberating spirit of the Church is indissolubly linked to its existence as an organised body’.

Teilhard’s vision of the Church is clear: ‘No longer simply the teaching Church but the living Church: germ of super-vitalisation planted in the noosphere by the historical appearance of Christ Jesus. Not some parasitic organism, duplicating or deforming the human cone of evolution but an even more interior cone, impregnating, occupying and gradually sustaining the rising mass of the world and converging concentrically towards the summit.’

The sacraments of the Church bring Christians into dynamic relation with the Risen Christ, above all, the sacrament of the Eucharist which assimilates Christians in their humanity to the glorified humanity of Christ and makes them partakers in Christ’s transforming action in the world.

It is by means of the Eucharist that the Church gradually divinises the world. Teilhard reminds us: ‘Adherence to Christ in the Eucharist must inevitably, ipso facto, incorporate us a little more fully on each occasion in a christogenesis which itself … is none other than the soul of universal cosmogenesis.’

By analogy, Teilhard sees the consecration extending to the entire universe which becomes the Body of Christ. ‘This is my body … ‘ This is the theme he develops in ‘The Mass on the World’ (1923).

Teilhard and the Catholic Church

When Teilhard speaks of the ‘Church’ he means the ‘Catholic Church’ – the community of local churches in communion with the Church of Rome whose bishop is the successor of SS Peter and Paul, Princes of Apostles.

In saying this he recognises that ‘there are doubtless many individuals who love and discern Christ and who are united to him as closely (and sometimes even more closely) than catholics … [but they] are not grouped together in the “cephalised” unity of a body which reacts vitally, as an organic whole, to the combined forces of Christ and humanity. These individuals are fed by the sap that flows in the trunk without sharing in its elaboration and youthful surge at the very heart of the tree.’

Teilhard sees the lateral branches becoming united with the central trunk. But this does not involve a return to the past. ‘The past is past. We must build ahead.’ He does not see the movement towards union involving in any way ‘fusion’ or absorption of other ‘confessions.’ Nor does he look backwards to the Church before the East-West split in the eleventh century or to the Western Church before the Reformation in the sixteenth.

On the contrary, he foresees a mutual enrichment in the assumption of values peculiar to each community in line with the principle of ‘differentiated union’ or, in another form, of ‘personalised love.’ In effect, if the Church is the ‘phylum of love,’ it is through the grace of Christ that it has the power to integrate, personalise and carry all things to God who is love. The Catholic Church alone can play this role.

‘If Christianity is indeed destined, as it professes and feels, to be the religion of tomorrow, it is only though the living and organic axis of its Roman Catholicism that it can match and assimilate the great modern currents of humanitarianism. To be catholic is the only way of being fully and completely Christian.’

The Catholic Church, however, must not simply seek to ‘affirm its primacy and authority but quite simply present the world with the Universal Christ, Christ in human-cosmic dimension, as animator of evolution.’

Ecumenism

For Teilhard, therefore, we must work towards an ecumenism open not only to Christianity but also to other religions because all religions of inner necessity converge on the Cosmic Christ and are destined to find their completion in the single Church of Christ.

Teilhard remained firmly opposed to any form of syncretism, e.g. Arnold Toynbee with his forecast of a future merging of major world religions. Teilhard remains faithful to the religious tradition from which he springs but he is no less deeply committee to an ecumenism that he sees ‘inevitably linked to the psychic maturation of the earth.’ And he finds himself asking ‘whether the only two effective ways of ecumenism might not be: (1) an “ecumenism of the summit” – between Christians – to bring out an ultra-orthodox and ultra-human Christianity on a truly cosmic scale, and (2) an “ecumenism of the base” – between men and women in general – to define and develop the foundations of a “common human faith” in the future of humankind.’ But, he adds, ‘faith in humankind does not seem to me capable of being satisfied without a fully explicit Christ. Any other method would, I fear, only produce confusion or syncretisms without vigour or originality … What we lack is the clear perception of a well-defined (and real) “type” of God and an equally well-defined “type” of humankind. If each group maintains its own type of God and its own type of humankind … no agreement can be taken seriously: it will do no more than produce equivocations or pure sentiment.’

A true ecumenism, he believes, must include: (1) a clearly defined God, the Cosmic Christ of St Paul and St John; (2) an equally clearly defined humankind, humankind as the spearhead of life at the present stage of evolution on earth; (3) a clearly defined Church, a Church seen as the ‘central axis of universal convergence’ in which ‘the Cosmic Christ continues to develop his total personality in the world.’

He sees two dangers: first, reducing Christianity to the ‘lowest common denominator’; second, seeking a certain ‘primitive purity’ by turning the clock back two thousand years and ignoring the role of the Church in history as the community of salvation willed by God in the course of time.

Three convictions represent for Teilhard the very marrow of Christianity: (1) the unique significance of Homo sapiens sapiens as the spearhead of life at the present stage of evolution on earth; (2) the axial position of catholic Christianity in the convergent fascicle (or bundle) of human activities; and (3) the essential consummating function assumed by the Risen Christ at the centre and summit of creation.

He looks to a progressive ascent of a humankind still in its infancy towards greater consciousness and greater unity, towards a pole of universal amorisation which he sees as none other than the Eternal and Living Christ.

His message is to the Church is clear. Christianity has stopped being infectious: ‘We have stopped being contagious because we no longer have a living conception of the world … ‘ And this because the Church of his day was no longer in tune with the hopes and fears of modern men and women. It was no longer able to demonstrate Christianity’s cosmic and planetary purpose. His life’s work was devoted to remedying this defect.

‘The essential contribution of Teilhard,’ writes Cardinal Jean Daniélou SJ, ‘has been to show that the results of modern science which he knew better than anyone else agrees more with a spiritual and christocentric vision of history than any materialist interpretation. He has opened up Christian faith to those trained in modern science. And he has helped theologians rediscover the true value of time in Christian revelation … In this he joins with the Early Fathers like Irenæus and Gregory of Nyssa.’

Conclusion

The evolutionary process has come a long way over the last twelve to fifteen thousand million years. It still has a long way to go. But Teilhard is confident of the place of the human species in that process. But, he rightly reminds us, the human species ‘is still only at the dawn of its existence.’ As species we may well be the present spearhead of the evolutionary process in our small corner of the universe. But we should never forget that this gives us a uniquely privileged position among all living things in a world in which we are relative newcomers – on the twenty-four hour evolutionary clock we did not even appear until two seconds to midnight!.

We must remember that we are responsible for what we make of the world. This responsibility follows from the nature of reflective consciousness. ‘We not only know that we know: we reflect.’ We alone can observe and we alone can reflect upon ourselves and upon the universe of which we are a product.

We can give meaning to the universe as we know it. But we are no longer simple spectators of evolution. We are its artisans. We hold the fate of the world in our hands.

Teilhard’s wholistic approach is based on faith in Christ but in both form and tradition it represents a conscious transposition of Christian faith and traditional theology into the language and dimensions of creation and becoming – from the language of cosmos into the language of a cosmogenesis which finds its completion in an omegagenesis or, more precisely, a christogenesis.

By following the curve of evolution Teilhard sees a gradual ascent emerging, groping, step by step, from matter to life, from life to spirit, from spirit to God. The final step – what he calls the ‘ultra-human’ or Point Omega – is something he believes science can quite legitimately postulate as the point of convergence of all the dispersed lines of evolution. He sees here the emergence of choice. He sees, in effect, what he calls ‘the pole of consolidation’ of evolution being on the side of spirit – not matter.

Such a reversal of the materialist thinking of his time is fundamental to the teilhardian vision of synthesis. His view of an ascending evolution – ‘pulled from above’ and ‘pushed from below’ – is a response, not only to the demands of science, but also to the fundamentals of faith.

Point Omega is no simple hypothesis – much less some sort of absurd ‘gamble’. It is a pole which is ‘bio-psychologically required by the evolution of a mass of reflective life.’

Teilhard has been criticised for making the sort of extrapolation which may be thought excessive compared to the cautious affirmations of ‘positivist science’. But Teilhard never divorces the mystic and the scientist. At the same time he refers to what is ‘verifiable in the field of phenomena’. His vision takes account of phenomena without becoming bound by the ‘rigorous canons’ of science.

His theological reflections are developed in perfect harmony with his vision of the Cosmic Christ. He believes the entire scientific and phenomenological ‘apparel’ of evolution serves no other purpose than providing a means of expressing in universal terms the ‘Ever Greater Christ.’ He transposes Christian faith and dogma in terms of universal evolution because he is convinced the Biblical Christ contains a cosmic element that has been neglected by historical theology. And this, in large measure, thanks to the work of Teilhard de Chardin who envisions a gradual christification of the universe. This is the vision that takes final shape in his last essay ‘The Christic’ (1955): ‘The Christ of Revelation is none other than the Omega of Evolution.’

Teilhard is the western mystic whose thought comes closest to the new systems biology. He tries to integrate his scientific insights, his mystical experiences and his theological ideas into a coherent world view that is dominated by process thinking and centred on the phenomenon of evolution. Darwin and Wallace plunged the human species back into the heart of nature where it belongs. Teilhard enabled us to see ‘the heart of Christ at the heart of matter.’

His ideas show remarkable similarities with systems theory. Its key concept is the theory of ‘complexity-consciousness’ which holds that evolution proceeds in the direction of increased complexity and that increasing complexity is accompanied by a corresponding rise of consciousness culminating in our small corner of the universe in human spirituality. The process, however, is cosmic in scope. ‘Cosmic consciousness,’ says Fritjof Capra, ‘is the self-organising process of the entire cosmos.’

Catholic writers like Jean Daniélou, Bruno de Solages, Henri de Lubac, Christopher Mooney, Gérard-Henry Baudry, Robert Faricy, James Lyons, Emily Binns, André Dupleix and many others are wholly convinced of the possibility of reconciling teilhardian positions with traditional catholic doctrine. And Alois Guggenberger is convinced we have remained attached far too long to an outworn static view of the cosmos: ‘The Greek idea of the cosmos as something fixed and static … must be eliminated … Only a transposition can help us and this is the new Copernican revolution Teilhard wants to bring about.’

René d’Ouince SJ sees Teilhard as ‘a prophet on trial.’ … ‘Almost certainly his “ideas” and especially his cosmology will, like all cosmologies, become dated. What will remain is that at a particular moment of history, in a particular cultural milieu, a particular believer had a vision of the undoubted grandeur of the world. After a certain period of decline I believe that the influence of Teilhard will take on a new lease of life. He will be read as we read the great classics.’

Teilhard is not always easy to read – in French or in translation – but he continues to have a profound effect on those who look to a future that could be rather than a past that never was. One of the leading pathfinders of the twentieth century, he sees himself as ‘a pilgrim of the future on my way back from a journey made entirely in the past.’ … ‘The past,’ he continues elsewhere, ‘has revealed to me how the future is built. And preoccupation with the future tends to sweep everything else aside.’

‘I, Lord, for my very lowly part, would wish to be the apostle and (if I dare be so bold) the evangelist of your Christ in the universe.’ … ‘What I am putting before you,’ he says, ‘are suggestions rather than affirmations. My principal objective is not to convert you to ideas which are still fluid but to open horizons for you, to make you think.’ And he concludes: ‘If I have had a mission to fulfil, it will only be possible to judge whether I have accomplished it by the extent to which others go beyond me.’

‘Glorious Christ,

the divine influence that is active in the depths of matter

and the dazzling centres where the fibres of the manifold meet:

power as implacable as the world and power as warm as life,

you whose forehead is of the whiteness of snow, whose eyes are of fire,

and whose feet are brighter than molten gold, you whose hands imprison the stars;

you are the first and the last, the living and the dead and the risen again;

it is to you to whom our being cries out a desire as vast as the universe:

“In truth you are our Lord and our God”.’